Super Maul

Day 1. Arriving at the rookery, the barking is loud, varied, sometimes guttural and nasally, otherworldly, and pretty funny. The sound fills the air. Once they see us, a bunch of them slide into the water en masse, and the water roils. I have to remind myself they aren’t going anywhere, so strong is my urge to jump in the icy water right then and there, gear or no gear.

They are definitely not going anywhere. It’s January, and this is when the Steller sea lions are hanging out at Hornby Island. That’s why we’ve made the journey that took one border crossing and three ferry crossings.

We descend along the anchor line, which takes us to about 50 fsw. That allows time to set up strobes and check camera settings before moving up slope to meet the marauders.

I want to be in the fray. When I had been in the water at a Steller sea lion rookery back in 2003, I was nervous because I didn’t know anything about their behavior, so I hung back. This time I’d been briefed extremely thoroughly and the moment I saw them, I wanted to be inside the melee, I wanted total sea lion chaos. We’d been told that if you kneel on the bottom, they will be all over you. If you lift up off the bottom, for whatever reason, their attentions wander. Maybe they can sense helpless playmates when they see them.

Our multiple briefings left me feeling confident. So I moved around until they found me. Then I hunkered down.

Over the course of the dive, nearly every accessible body part was tasted and tested, nibbled and nudged, tugged and teased, pulled and pinched, and just this side of bit. Well, yeah, bit.

One bit my butt (left side). I felt them test out my hamstrings. I felt them on my calves. I could also feel them tugging on various pieces of scuba gear, and at one point I heard bubbles escaping my BC — presumably, though I’m still not entirely sure.

One bit at the side of my mask. That was the most tenuous it got. Otherwise, the biting was tolerable, because I knew they would never really chomp down. So we were told.

One kept testing my bicep, over and over. Not too hard, but hard enough for me to wonder if it was impressed. (Did I flex? You’ll never know.)

One worked its way down my forearm slowly to my hand, and I started to imagine what would happen to my fingers if it kept going. So I made a fist to be safe.

At one point I could feel both of my fins simultaneously pulled by different animals.

The third mauling of the dive was the most intense. They were on me, under me, next to me. One settled in with his face next to mine and just stayed there a while. I could feel them everywhere around me.

Beyond body parts, twice they became tenacious about my flash sync cord. The first time the sea lion pulled for a while then gave up. The second time, the sea lion successfully removed the sync cord from my secondary strobe and pulled on it for what seemed like ever. I knew there was not a thing I could do about it. I hoped the cord would be okay, but I knew it might not. The sea lion pulled and pulled and pulled. Funny how something so small could capture their attention. Eventually the sea lion let go. But they were still all around me, so I did not want to incite by reaching out for it. And sure enough, it grabbed it again and kept pulling some more. Eventually they had to go up for air. Shockingly, the fragile sync cord remained intact. That speaks to how gentle they can be in their tenacity.

More than once they tried to swim away with my strobe in their front flippers. Fairly dexterous, those flippers, from my very close-up perspective.

I flipped my camera around for selfie photos with them and tried to gauge when to snap by activity level, by feel, and by reflection in my dome port. Most of all I wanted a shot of one with its mouth on my head. But both times when I could actually feel a mouth over my head, I was so in awe of the fact that a sea lion had its mouth on my head that I forgot to snap the shot. The first time it was mild. Later, the second time it happened, I could actually feel teeth.

More than once a group of 10 or 15 or 20 swam past, all in tight formation, completely in sync like one beautifully orchestrated machine moving effortlessly but with such great power and speed, 20 parts to a single torpedo.

After I’d had enough fun (and enough ocean in my drysuit from a poorly sealed wrist seal), I headed back towards the boat. I reached the boat, handed up my camera, then went to remove my fins, and one of the fin straps was totally undone. Thanks, guys.

When I went to remove my BC from my tank, one of my two tank straps had been undone as well. Wily. Wily sea lions.

Grand Maul

Day 2. After reviewing my photos from day 1, I wanted more-better head shots. That is, a shot of them with their mouths on my head. This would be “be careful what you wish for” day.

We arrived at Norris Rock, and immediately they began swimming and porpoising out towards us, like a giant pack of super excited dogs, boundless joy, leaping into unabashed play.

Not much time to set up my camera this go-round, as they met us at the bottom. Actually, they met us on the way down.

And in almost no time, they were on me. And they seemed especially interested in my head today. (Be careful what you wish for!) More than one in succession seemed to read my mind and wanted to get their jaws around my noggin. I kept telling myself they’re just checking me out, they won’t bite down too hard – thinking these thoughts as they were on the extreme verge of not biting down too hard. Pretty sure I came away with mild teeth-shaped bruises like a crown around my crown.

In fact, they came so quickly and played so hard from the git-go, that I ended up putting my arm up over my head more than once just to fend them off. Forget the photos. Tomorrow’s another day! They were playing harder than day 1, no doubt about it.

After only a few minutes and enough head-shots to satisfy myself for the day, I raised up off the bottom. Instantly they became less interested: hovering above the bottom is like going into safe mode. So I swam around a bit watching them interact with some of my dive friends. It is an underwater mammalian ballet (er, modern dance?), to see them swim so fast, so gracefully, and yet so playfully.

One in particular held me rapt. It spun as it swam, like a propeller, just spinning and moving slowly forward. It reminded me of the one really creative kid who goes off by himself and dances or paints a beautiful scene while everyone else is busy doing the same thing everyone else is doing.

Another miniature scene that played out was a very small sea lion, who first went over to buddy Joan and just lay on the bottom posing perfectly for her for the longest time. It seemed not much older than a baby, and oh so gentle. When it did eventually swim away, she gave some excited hand signals that translated into something like “WOW WOW WOW! DID YOU SEE THAT??”

After witnessing Joan’s interaction with the little one, I wanted some of that. Before long, a small one swam in front of me, and it kept swimming in circles right before me. It might have swam 6 loops – it seemed to be asking me to join in. It had a game in mind, but I wasn’t catching on. So after trying to teach me the game, it decided I was a lame wallflower and swam off. I was a lame wallflower.

This day I decided to see what it was like to be in with them at the surface. Happily, buddy Myra and Joan decided to do the same thing at the same time, so I did not feel alone in what really does feel like a crazy endeavor. They are so big, and the idea of swimming right into a big mass of 20 or more of them doesn’t sound like the brightest idea in the world. But everyone had said that they maul you the least at the surface. Time to find out.

Overall they maul you the least at the surface (maybe?). But I very nearly had my mask ripped off at the surface. So on this day my jury said that they generally don’t interact as much up top, but when they do, anything goes. When I felt the chaos that included my mask almost being removed, I put my hand up to hold it in place then just wait for the sea lions to finish doing whatever it was they were doing. They pushed me down and around a bit and tugged on various parts. But I’ve done Ironman swims, and once during the Honu 70.3 Half Ironman in Hawaii, I had two swimmers, one on either side of me, converge in the space where I had been, which meant I went down. The sea lions had nothing on the washing machine that is the Honu 70.3 swim. Pshaw! Piece of cake! Sea lions, shmea lions!

Darth Maul

Day 3. The sea lions seemed kind of lazy, and the clouds and grayness of the morning echoed the slow feel. We splashed, and pretty quickly I spotted a squadron of the mammalian torpedoes swimming together down towards what looked like an underwater amphitheater. I followed to take a look, and by the time I arrived, every one of them – maybe 15 – had their heads stuck under a ledge. Just bodies sticking out all in a row, like keys on a piano.

the drawing I made of them in my logbook

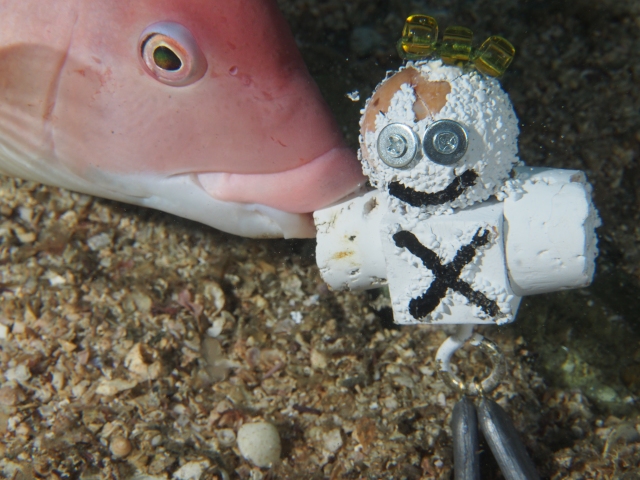

Pretty soon they began emerging from their little cavern, and nearly every one of them had sea stars or sea cucumbers in their mouths. This was their toy chest! They would toss their toys out into the water and grab them again, nudge each other with them to incite more play, carry them around a bit and then drop them. Essentially behaving like puppies in the toy basket. They had no interest in eating these sea decorations, just playing with them.

I watched one swim to the top of the ledge and very gently set its sea cucumber down, like placing it carefully back into the toy box. This is the gentle child who will get bullied in school.

I stayed down in the small arena waiting for their return. The big group did not come back, but one sea lion I ended up seeing several times throughout the dive approached me. It was easily identifiable by the two vertical white marks on either side of its nose. I call this one Nosey. Nosey was on the large side of being a juvenile, and it gave off a vibe that bordered on aggressive (or creepy, if you read too far into it). I assumed a more protective demeanor – that is, I wasn’t going to drop to the bottom, where I would be most vulnerable – and in fact, I didn’t even want to let Nosey get his teeth on me at all. Despite all I’d learned, I had the feeling that this one wanted to play with me, wanted to play hard, wanted to make me is special friend. I don’t mean this in a kind, gentle way. So I stayed off the bottom and moved any time he came towards me – if he came towards my right side, I swam in a circle to the right to stay out of the reach of his mouth. Now, if he’d really wanted to catch me, he certainly could have. But what ended up happening was I continued this spinning motion, swimming in circles with him swimming in circles around me. We did this for several spins (which takes a lot of gas and gets exhausting fast), then I noticed he started swimming in the cork-screw fashion I’d seen one of the little ones do. My interpretation of all this was Nosey thought that I was trying to teach him a new game. Which was a pretty sweet feeling, despite how creepy he was. Eventually, he needed air so I too got a breather.

Over the course of the dive, I saw Nosey about three more times. Each time, he had the same intense manner about him, and each time I did not let him touch me. Spooky child!

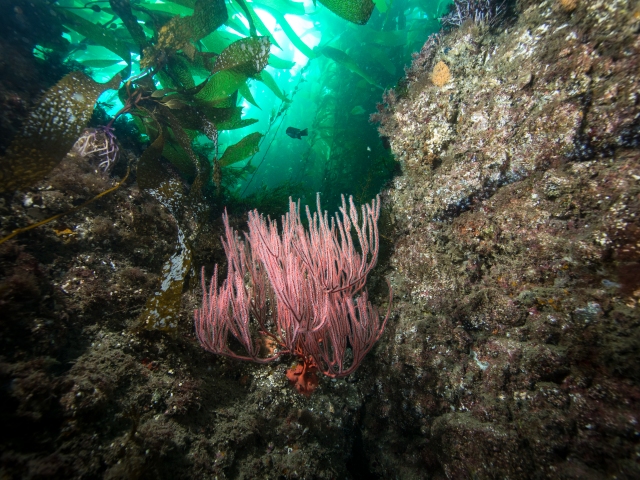

After the piano keys and Nosey left, things were quiet for a long while. I started to think my last dive sea lion dive of the trip might be a bust. I swam around a bit – the site really was quite pretty. And the water was green and stunning, and the sun was breaking through on top. I was ready for a sea lion to swim into my perfect green water with the sparkly sun beams on top. But they didn’t, not en masse. Just a couple teasers before everyone disappeared.

I swam up and towards the island, and before long, we were getting visited again, but it was not as intense as the prior two days. The sea lions were more dispersed, to be sure. I was starting to think the trip would end with a fizzle.

But then they reappeared, and there was no shortage of sea lion buddies in every direction.

I had already decided I wanted some shots at the surface, so I headed up into the gaggle of them.

Forget everything I said about them leaving us alone at the surface. For the first time, without any question whatsoever, I was a living, human chew toy. There were so many, and they were everywhere at once, pulling, pushing, biting like crazy everywhere. It was over the top, and it seemed it would never end. I was a tug-of-war toy, I was a rubber chicken, I was a bouncy ball with a treat inside. You name it, and that is what I was, and all at once, and on and on.

I kept snapping photos as best I could, though half the time they would push my camera sideways before I could click. Once they managed to turn the camera off. Another time they turned off my strobe. And for the love of Pete, they bit my head over and over and over. To the point where I just shut my eyes and hoped they’d get bored, because clearly there was no escaping.

And yet. After they finally left – finally! – for a moment, I instantly began looking for more. I had to remind myself I had been wanting to finish. I reluctantly began swimming towards the boat and away from a truly incredible source of fun, kept turning around to see if they were following me, already regretting leaving before the last possible moment.